MEXICO CITY (AP) — Independent investigators leaving Mexico after eight years searching for answers to the 2014 disappearance of 43 students from a teachers’ college say they experienced a “double reality” unlike anything they ever encountered in other international missions.

“It’s like you’re in a movie, things are happening and you say, ‘This isn’t real,’” said Spanish physician Carlos Beristain. He said they had to figure out together what was true and what wasn’t to make quick decisions and avoid being fooled.

“It was a constant exercise, very tiring, very stressful,” he said, adding that often the most documented purported details in the case ended up being false.

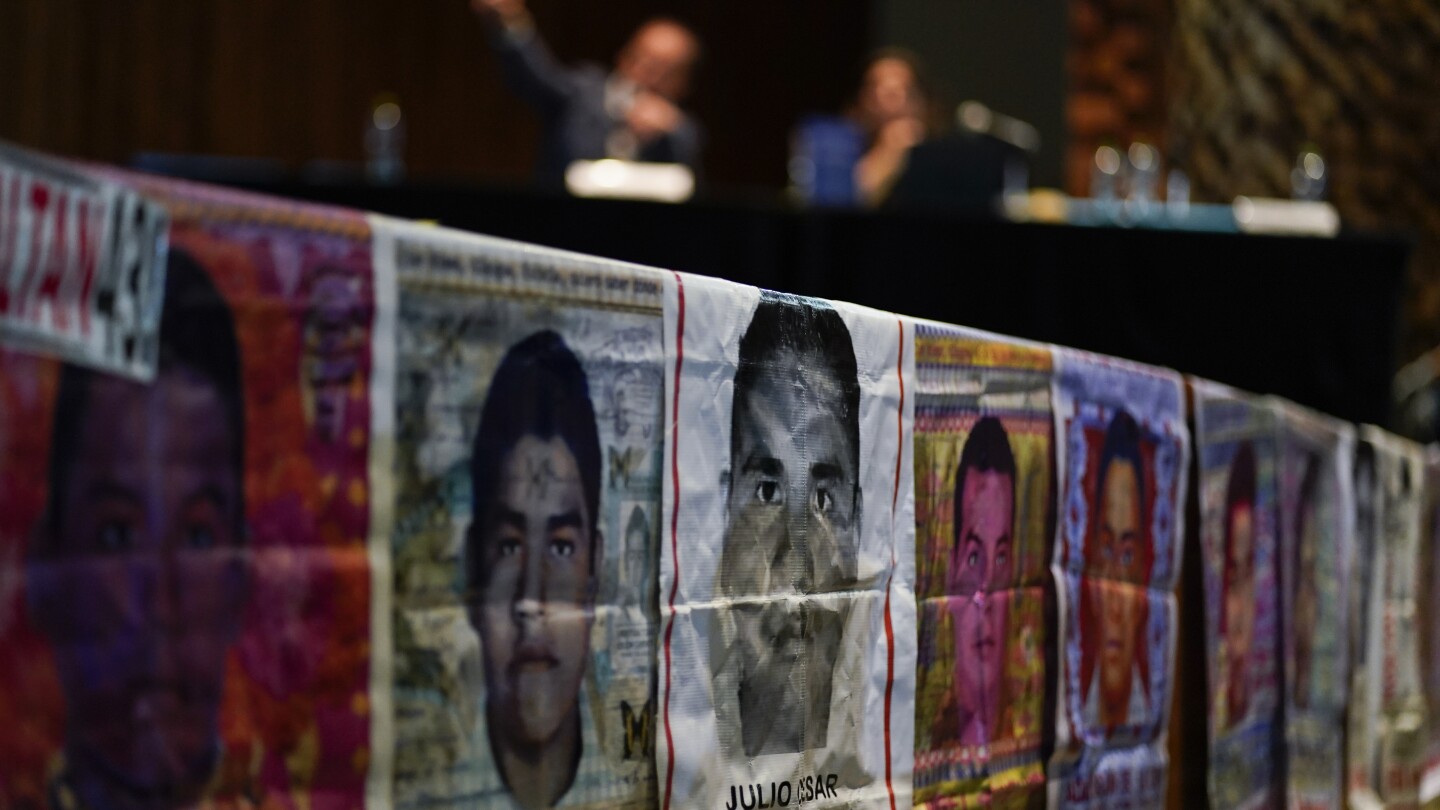

Beristain and former Colombian prosecutor Ángela Buitrago, who were interviewed by The Associated Press just before they left Mexico on Monday, were two members of the team sent by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2015 to help clear up the so-called Ayotzinapa case. On Sept. 26, 2014, the 43 students in the southern state of Guerrero were taken off buses in the town of Iguala by authorities and handed over to a local drug gang.

Last year, a government truth commission concluded it was a “state crime,” noting the involvement of local, state and federal authorities in the students’ disappearance and subsequent cover-up in collusion with organized crime.

Beristain and Buitrago were the last remaining members of the original five-person team. While the administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said it was willing to extend their mandate, Beristain and Buitrago decided that with the military still putting obstacles in their way, there was little reason to continue.

They said they were grateful for the students’ rural families who gave their work purpose and who from the first moment asked only two things: for the team not to lie to them and to not sell out. The investigators only understood the second request much later when they became conscious of the corrupting power of Mexican institutions.

The group, which originally included former Guatemala Attorney General Claudia Paz y Paz, Chilean lawyer Francisco Cox and Colombian lawyer Alejandro Valencia, served two periods in Mexico. The first was 14 months during the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto, which did not renew their mandate after the group showed that his administration’s account of what happened to the students was fabricated.

The second period came during the current administration of López Obrador, which arrived with high expectations because of his promise to find out what really happened regardless of where the investigation led.

The prosecutors did make progress — a dozen soldiers and a former attorney general were arrested — but the army and navy continued to hide information, the investigators said.

Buitrago recalled spending months in a basement reading the 85 volumes — each more than 1,000 pages — of the government’s investigation with other team members. She said that every time they pointed to something that didn’t quite line up, something new would appear to clarify it.

For example, they questioned how few kilograms of wood could be used to keep a huge bonfire going that the government said was used by gangsters to incinerate the students’ bodies in the rain. Within a week, a new suspect had been arrested who, coincidentally, confessed to having used more wood as well as tires and gasoline, Buitrago said.

“It got to the point that they (colleagues) asked me to not say what was missing anymore,” she said.

The investigators were also constantly amazed how the suspects always seemed to “voluntarily” confess to Mexican authorities of having participated in the massacre in almost the same way despite having been picked up on charges of drug or weapons possession. Or how one suspect who later confessed to participating had gone to the federal prosecutor’s office for some other errand where he was promptly arrested.

“This never happens in a criminal life,” Buitrago said.

She described that early period as like a charade, where on one hand the authorities tried to impress and please the investigators, while behind the scenes officials did everything possible to keep up their fabricated version of events.

There were authorities who helped them, despite the fear of repercussions, but others tried to intimidate them, Buitrago said.

The more they dismantled the original official version — described by the government as the “historic truth” — the more the investigators felt harassed.

“I started not being able to sleep,” Beristain said. “It was evident that there was a strategy to mislead us that wasn’t very explicit, so you couldn’t complain about it, but it was evident.”

The current administration reanimated the effort by inviting the team back and creating a truth commission. There were some key arrests, but at times the investigators felt rushed and lacked the necessary supporting evidence. The military continued blocking access to some information despite López Obrador publicly ordering it to cooperate, they said.

They did eventually obtain evidence of interrogations using torture inside navy facilities. Buitrago said one of the worst aspects of the investigation for her was watching hours of torture employing electricity, water, plastic bags and threats of hauling in suspects’ wives to be raped.

“I spent a week and a half in which I felt suffocated,” she said.

The students’ families and the way they maintained their dignity were the constant throughout, the investigators said. They became very close and at the end joked that they would take the investigators’ passports so they couldn’t leave.

The families will continue their search for answers. Asked if there are people who really know everything that happened, Buitrago and Beristain replied in unison: “Yes, a lot.”