LONDON (AP) — The world has always loved a golden couple, especially when there are hints of trouble in paradise.

Decades before millions tracked every move of Harry and Meghan, William and Kate or Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce, it was the turbulent union of actors Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor that set gossip columns aflame.

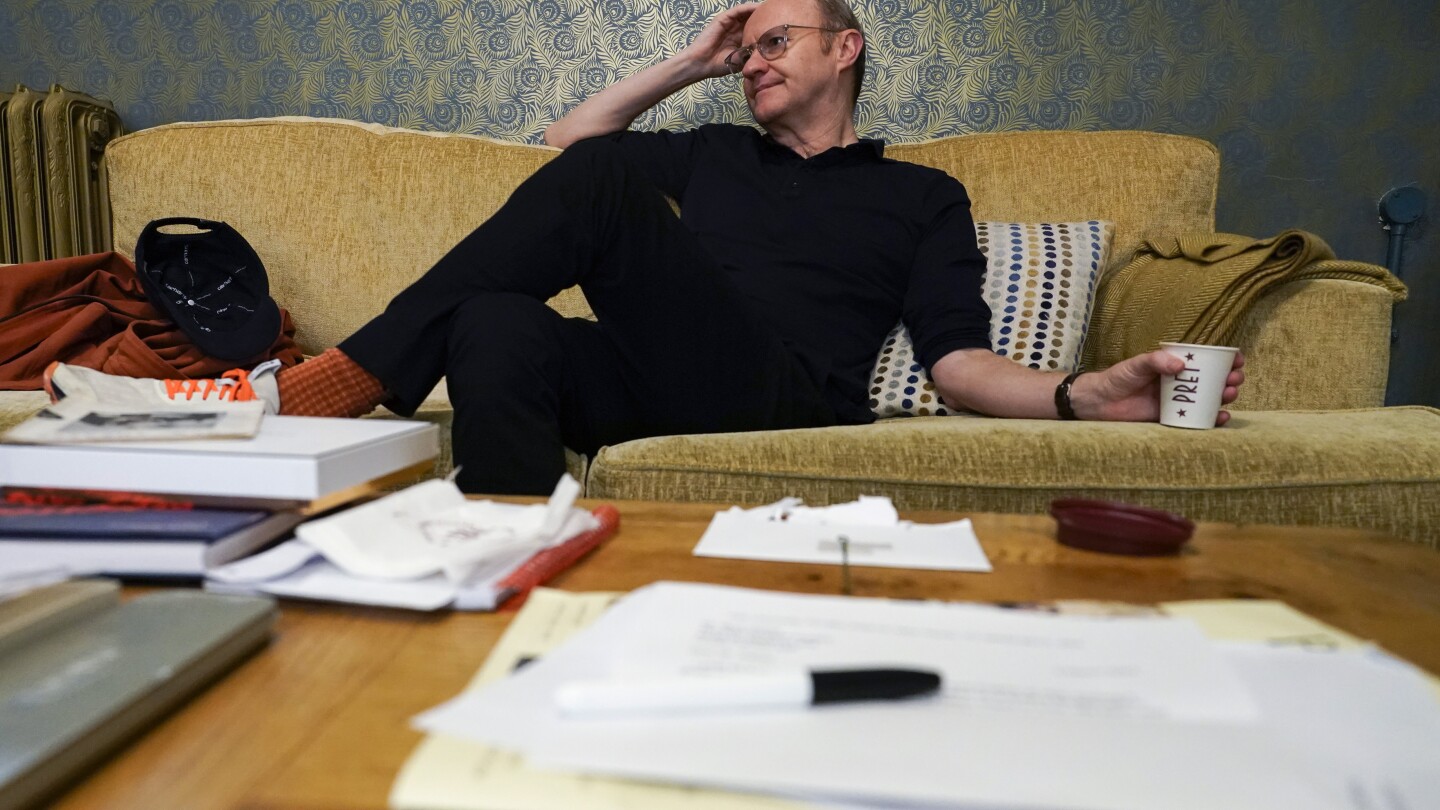

“In a time when the world was much less connected, they were like gods,” said Mark Gatiss, who stars in “The Motive and the Cue,” a hit play about Taylor and Burton in their 1960s heyday. “They really were. People hung off their every divorce.”

“The Motive and the Cue” has had two sellout runs in London and will be broadcast in cinemas in Britain and internationally starting Thursday as part of the National Theatre Live series.

The play charts the rocky creation of a now-legendary piece of theater, a 1964 Broadway production of “Hamlet” in which Burton played William Shakespeare’s tormented prince. The production was a triumph, but it was almost a disaster. Jack Thorne’s backstage drama depicts the tensions between Burton, played by Johnny Flynn, and the play’s director, John Gielgud, played by Gatiss. Tuppence Middleton forms the third point in the central triangle as Taylor.

Directed by Sam Mendes — returning to his first love, the theater, after a film-dominated period that included James Bond thrillers “Skyfall” and “Spectre” — it’s a witty and moving look at fame’s fickleness and cost. It shows Taylor and Burton essentially confined to the gilded cage of their New York hotel suite.

The brooding, velvet-voiced Burton was a megastar but craved artistic credibility. Gielgud, a dashing leading man in the 1920s and 30s, was, Gatiss said, “completely washed up.”

“Gielgud was a relic. He did this because it was the best offer he’d had in a long time.”

The twist in the tale came in the years that followed. Burton’s heavy drinking blighted his career, and he died in 1984 aged 58. Taylor also did her best work when young, married eight times — twice to Burton — and died in 2011.

Gielgud, meanwhile, had a career renaissance that brought Hollywood fame, an Academy Award — for playing Dudley Moore’s butler in “Arthur” — and the status of elder statesman of British drama. He died beloved and lauded in 2000, aged 96.

Gielgud, Burton and Taylor are increasingly figures from history, but the play has struck a chord even with audiences who don’t remember them.

“I had two friends come the other day — they’d never heard of any of the principals, incredibly,” Gatiss said during an interview in his dressing room at the Noel Coward Theatre. “But they got it, because of what it’s about. It’s about fame, it’s about reputation, it’s about legacy, it’s about fathers and sons.”

It’s also a love letter to the theater, especially to “Hamlet,” which a caption at the end of the play says has been played by an astonishing 250,000 actors. One of them was Gielgud, who performed the role in the 1930s in the same West End theater where “The Motive and the Cue” is running until March 23.

That coincidence tickles Gatiss, an actor-writer-director who played the great detective’s brother, Mycroft Holmes, in the BBC TV series “ Sherlock,” which Gatiss created with Steven Moffatt.

He has won rave reviews, and an Olivier Award nomination, for his understated and moving performance as Gielgud — “a mellifluous marvel,” according to The Observer; “the performance of his career” in the view of the Daily Telegraph.

If Gielgud was once considered a relic, it’s Burton who now seems an icon of a vanished age — one in which a Welsh coal miner’s son like him could break into the acting world.

Gatiss’ own love of drama was inspired by teenage trips to the theater in Darlington, near his childhood home in northeast England. He worries that a combination of cuts to arts education and the soaring cost of theater tickets is turning acting into a career for the privileged.

He’s enthusiastic about NT Live, which lets people see productions for the price of a movie ticket. “The Motive and the Cue” is the 99th production in the series, which began in 2009 and now broadcasts to 700 cinemas around the world. NT Live uses multiple cameras, tracking shots and close-ups to merge the immediacy of live theater and the intimacy of film.

“Access to the arts is becoming so strangled,” Gatiss said. “There are a lot of posh actors, in a sort of ‘Brideshead’ kind of way. It feels like we need a 1960s-type movement of getting working-class voices into the arts.”

“The great irony is, theater used to be the great democratizer,” he said. “It was as low as you could get. Actors were so disreputable. I think we maybe need to get back to that.”