CARACAS, Venezuela (AP) — For millions of Venezuelans and dozens of foreign governments, Edmundo González was the undisputed winner of the country’s July 28 presidential election.

But on Sunday, he joined the swelling ranks of once-prominent government opponents who have fled into exile, leaving his political future uncertain and tightening Nicolás Maduro’s grip on power.

The former presidential candidate arrived at a military airport outside Madrid after being granted safe passage by Maduro’s government so he could take up asylum in Spain. His surprise departure came just days after Maduro’s government ordered his arrest.

González, 75, burst onto Venezuela’s political scene less than five months ago. His candidacy was as accidental as it gets after opposition powerhouse María Corina Machado was barred from running and a handpicked substitute was also blocked.

In April, a coalition of more than 10 parties settled on González, who overnight went from being a virtually unknown retired diplomat and grandfather to a household name in whom millions placed their hopes for an end to more than two decades of single-party rule.

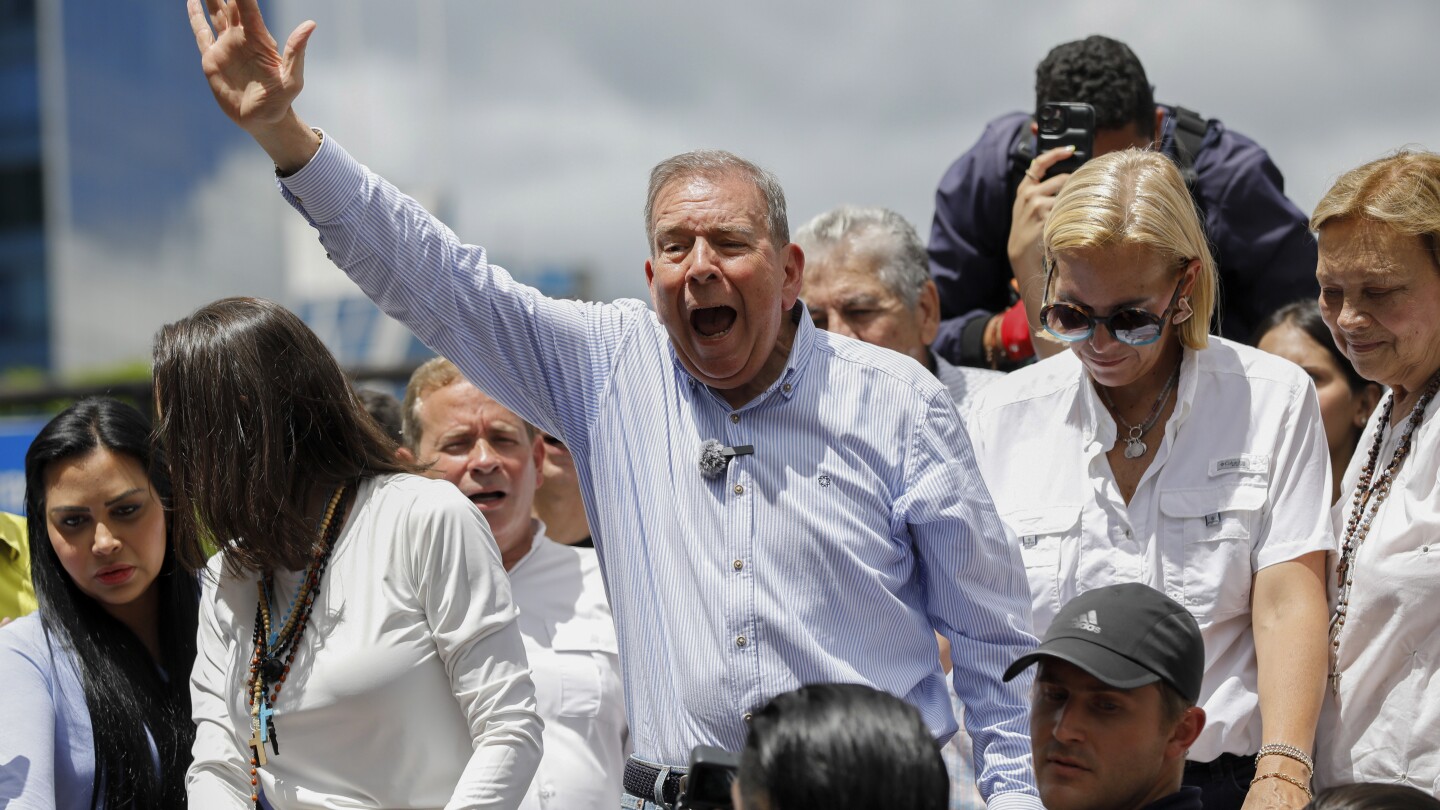

Accompanied by Machado, he crisscrossed the country in the final weeks of the campaign, energizing massive crowds of Venezuelans who blamed Maduro for one of the worst ever economic collapses outside a war zone.

Over 50 countries go to the polls in 2024

- The year will test even the most robust democracies. Read more on what’s to come here.

- Take a look at the 25 places where a change in leadership could resonate around the world.

- Keep track of the latest AP elections coverage from around the world here.

“Let’s imagine for a moment the country that is coming,” he told a crowd of cheering supporters at a rally in La Victoria, a once-thriving industrial city. “A country in which the president does not insult or see his adversaries as enemies. A country where when you get home from work, you know that your money has value, that when you turn on the switch, there will be electricity, that when you turn on the faucet, there will be water.”

The yin-yang strategy proved more popular than even many Maduro opponents had imagined.

Election was quickly disputed

Although the National Electoral Council declared Maduro the winner, the opposition’s superior ground game allowed it to collect evidence showing that it was actually González who prevailed by a more than a 2-to-1 margin. Foreign governments condemned the official results as lacking credibility. Even some leftist allies of Maduro withheld recognition, demanding that authorities release a breakdown of results at all 30,000 voting machines nationwide, as it has in the past.

In the weeks since the disputed vote, both opposition figures went into hiding amid a brutal crackdown that led to more than 2,000 arrests and the deaths of at least 24 people at the hands of security forces. González stayed out of public view while Machado appeared at sporadic rallies seeking to keep the pressure on Maduro.

Machado tried to put a positive spin on González’s departure late Saturday, assuring Venezuelans he would be back on Jan. 10 for a swearing-in ceremony marking the start of the next presidential term.

“His life was in danger, and the increasing threats, summons, arrest warrants and even attempts at blackmail and coercion to which he has been subjected, demonstrate that the regime has no scruples,” Machado said on X. “Let this be very clear to everyone: Edmundo will fight from outside alongside our diaspora.”

Candidacy came after career as a diplomat

González began his professional career as an aide to Venezuela’s ambassador in the U.S. He had postings in Belgium and El Salvador and served as Caracas’ ambassador to Algeria.

His last post was as Venezuela’s ambassador to Argentina during the first years of the government of Hugo Chávez, Maduro’s predecessor and mentor. More recently, he worked as an international relations consultant, writing about recent political developments in Argentina and authoring a historical work on Venezuela’s foreign minister during World War II.

His years in El Salvador and Algeria coincided with periods of armed conflicts in both countries. For a time, his whereabouts were tracked by locals in El Salvador, and he would get calls at home meant to intimidate him, with the callers saying they were aware that González had just arrived home.

Maduro on the campaign trail claimed — without evidence — that González was recruited as a CIA asset during that Cold War, which coincided with heavy U.S. military involvement in Central American country.

González had just returned to Venezuela’s capital, Caracas, from a trip to Spain to visit a daughter and grandchildren when opposition leaders presented him with the idea of becoming a candidate.

The subdued tone and poker face he forged as a diplomat cut a sharp contrast with boisterous, ego-driven politicians to which Venezuelans have long been accustomed. Maduro and his allies have taken his conciliatory tones as a sign of weakness. But that kind of language was among his many selling points to Venezuelans fed up with winner-takes-all politics.

“Enough shouting, enough insults,” González told supporters. “It’s time to reunite.”

___

Goodman reported from Miami.