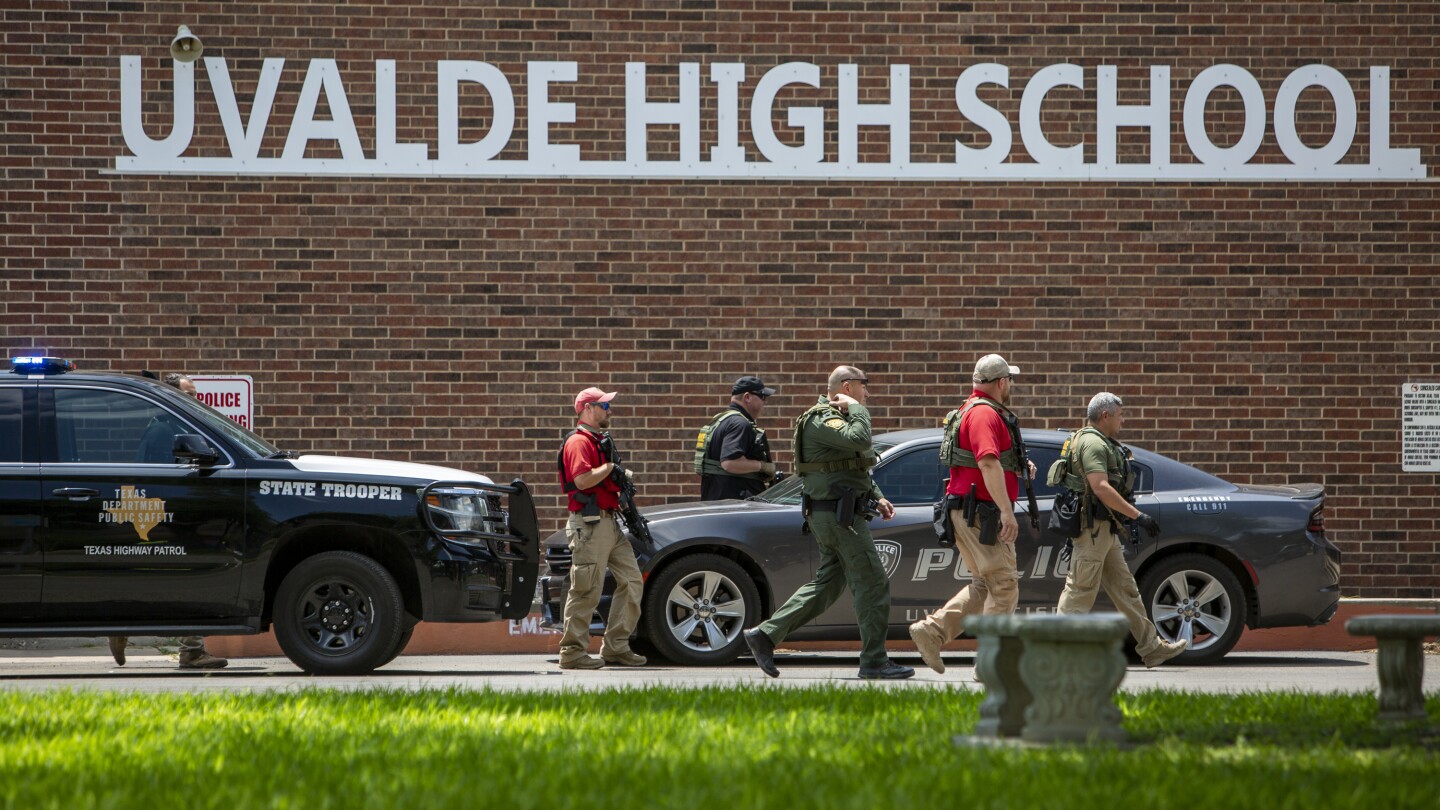

U.S. Border Patrol agents who rushed to the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas in 2022 failed to establish command and had inadequate training to confront what became one of the nation’s deadliest classroom attacks, according to a federal report released Thursday. But investigators concluded the agents did not violate rules and no disciplinary action was recommended.

The roughly 200-page report from the Department of Homeland Security does not assign overarching blame for the hesitant police response at Robb Elementary School, where a teenage gunman with an AR-style rifle killed 19 students and two teachers inside a fourth-grade classroom. Nearly 200 U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers were involved in the response, more than any other law enforcement agency.

The gunman was inside the classroom for more than 70 minutes before a tactical team, led by Border Patrol, went inside and killed the shooter.

Much of the report — which the agency says was initiated to “provide transparency and accountability” — retells the chaos, confusion and numerous police missteps that other scathing government reports have already laid bare. Some victims’ family members bristled over federal investigators identifying no one deserving of discipline.

“The failure of arriving law enforcement personnel to establish identifiable incident management or command and control protocols led to a disorganized response to the Robb Elementary School shooting,” the report stated. “No law enforcement official ever clearly established command at the school during the incident, leading to delays, inaction, and potentially further loss of life.”

Customs and Border Protection said in a statement that investigators “concluded none of the CBP personnel operating at the scene were found to have violated any rule, regulation, or law, and no CBP personnel were referred for disciplinary action.”

Families of the victims have long sought accountability for the slow law enforcement response.

Jesse Rizo, whose niece Jacklyn Cazares was one of the students killed, said that while he hadn’t seen the report, he was briefed by family members who had and was disappointed to hear that it held no one accountable.

“We’ve expected certain outcomes after these investigations, and it’s been letdown after letdown,” said Rizo, who is on the Uvalde school board.

The report’s authors said its purpose was to determine if agents complied with relevant rules and laws, and if anything could improve their performance in the future.

A Border Patrol agent who lined up behind other officers who breached the classroom described the scene as “mass confusion.”

“He was surprised by the number of people who responded to the incident and was unsure about who was in charge,” the report states.

Since the shooting, Border Patrol has largely not faced the same sharp criticism as Texas state troopers and local police over the failure to confront the shooter sooner. The gunman was inside the South Texas classroom for more than 70 minutes while a growing number of police, state troopers and federal agents remained outside in the hallways.

Two Uvalde school police officers accused of failing to act were indicted this summer and have pleaded not guilty.

Throughout the report, Border Patrol agents detail the confusion and lack of leadership that permeated the law enforcement response. Some agents commented that messages relayed via radio were at times incomprehensible because people talked over one other.

A Border Patrol agent assigned to help at the Civic Center, where families gathered to await information about their children, called it “a chaotic mess with parents, media, and law enforcement,” the report said.

Over 90 state police officials were at the scene, as well as school and city police. Multiple federal and state investigations have laid bare cascading problems in law enforcement training, communication, leadership and technology, and questioned whether officers prioritized their own lives over those of children and teachers.

A report released by state lawmakers about two months after the shooting found “egregiously poor decision-making” by law enforcement. And among criticisms included in a U.S. Justice Department report released earlier this year was that there was “no urgency” in establishing a command center, creating confusion among police about who was in charge. That report highlighted problems in training, communication, leadership and technology that federal officials said contributed to the crisis lasting far longer than necessary.

While terrified students and teachers called 911 from inside classrooms, dozens of officers stood in the hallway trying to figure out what to do. Desperate parents who had gathered outside the building pleaded with them to go in.

A release last month by the city of a massive collection of audio and video recordings from that day included 911 calls from students inside the classroom. One student who survived can be heard begging for help in a series of 911 calls, whispering into the phone that there were “a lot” of bodies and telling the operator: “Please, I don’t want to die. My teacher is dead. Oh, my God.”

The 18-year-old gunman entered the school at 11:33 a.m., first opening fire from the hallway, then going into two adjoining fourth-grade classrooms. The first responding officers arrived at the school minutes later. They approached the classrooms, but then retreated as the gunman opened fire.

Finally, at 12:50 p.m., a group led by a Border Patrol tactical team entered one of the classrooms and fatally shot the gunman.

Two of the responding officers now face criminal charges. Former Uvalde school Police Chief Pete Arredondo and former school officer Adrian Gonzales have pleaded not guilty to multiple charges of child abandonment and endangerment. A Texas state trooper in Uvalde who was suspended has been reinstated.

Last week, Arredondo asked a judge to throw out the indictment. He has said he should not have been considered the incident commander and has been “scapegoated” into shouldering the blame for law enforcement failures that day.

Uvalde police this week said a staff member was put on paid leave after the department finished an internal investigation into the discovery of additional video following the massive release last month of audio and video recordings.

Victims’ families have filed a $500 million federal lawsuit against law enforcement who responded to the shooting.

___

Gonzalez reported from McAllen, Texas, and Stengle reported from Dallas. Associated Press reporters Dave Collins in Hartford, Connecticut; Sean Murphy in Oklahoma City; Heather Hollingsworth in Kansas City, Missouri; Juan A. Lozano in Houston; and Nadia Lathan in Austin, Texas, contributed to this report.