SANTIAGO, Chile (AP) — Despite a boom in conservative populism in various parts of the world, Chileans closed an exhausting constitutional cycle by separating themselves from the extremes.

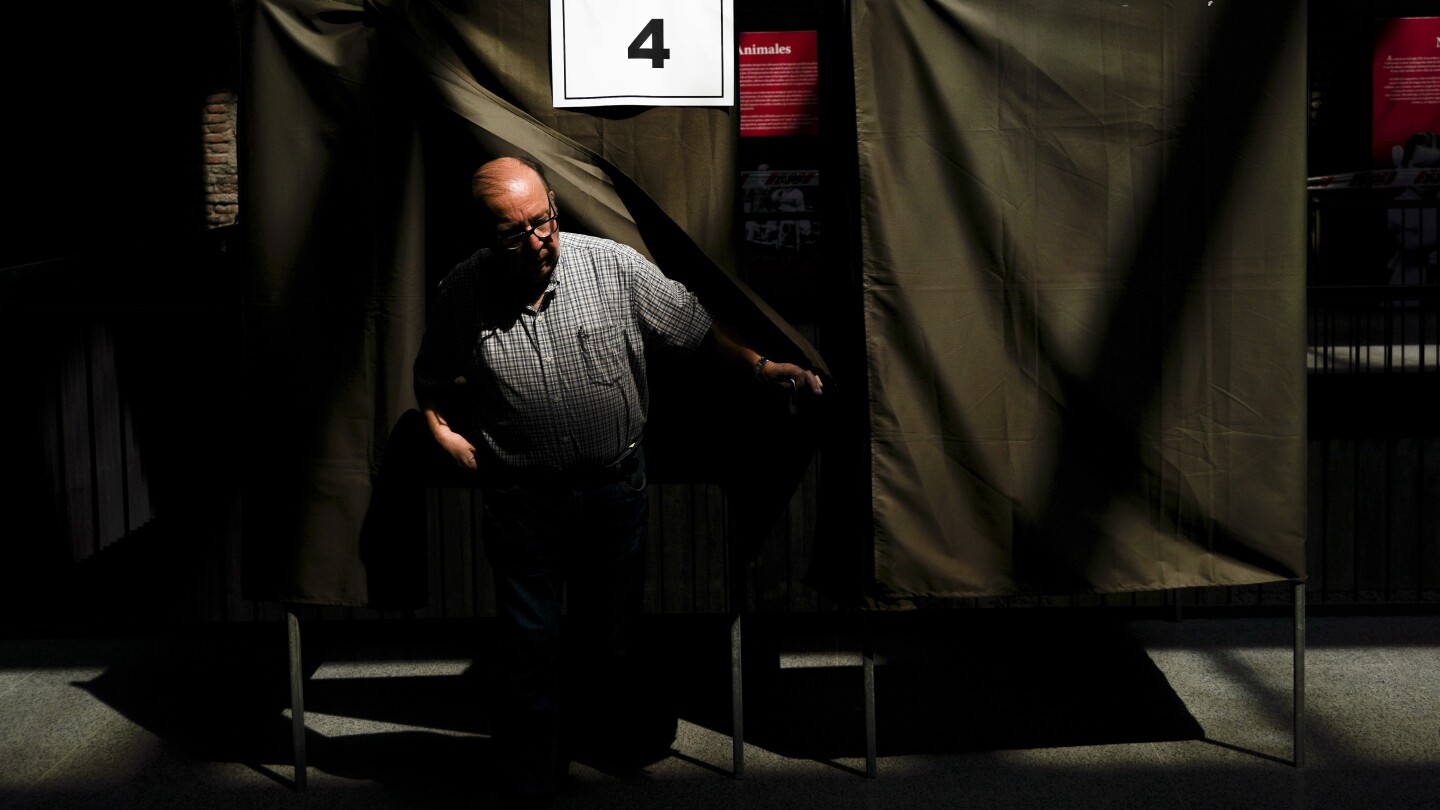

They voted Sunday to stick with the same constitution, a holdover from the dictatorship, that they had wanted to rewrite four years ago. The decision sent a clear message to the country’s politicians: get to work on the country’s most pressing collective needs within the existing legal framework.

Voters rejected a more conservative proposed constitution drafted by the right with 55.7% of the votes.

Barely a year earlier, 62% of Chilean voters had resoundingly rejected a proposed constitution from the other end of the ideological spectrum. Drafted by leftist sectors and supported by President Gabriel Boric, it was considered one of the most progressive constitutional initiatives in the world.

No one took to the streets to celebrate Sunday’s result. Chile will continue to be ruled by a constitution born of the military regime of dictator Augusto Pinochet, which has been reformed on some 70 occasions.

Analysts saw lost opportunities in which Chileans opted twice for drafting political agendas more so than a durable legal framework with room for diverse democratic options.

Marcelo Mella, a political science professor at the University of Santiago, said there were attempts to leave their own ideological mark and in the end everyone paid the price.

The first proposal “went too far, too fast on issues like plurinationality or unlimited right to abortion,” said Javier Couso, a Chilean constitutional scholar and professor at the University of Utrecht in Holland.

The second, on the other hand, went to the other extreme and opened the door to limiting abortion and intensifying free market policies, reducing the role of the state and its social policies. That would have been the opposite of what thousands of demonstrators demanded in 2019, launching the extended exercise to come up with a new constitution.

Couso said one lesson was that politicians tried to exacerbate a polarization that didn’t really exist among the people, who voted for moderation.

So Chile keeps a constitution from the dictatorship that is “legally valid, but repudiated by the citizenry,” Couso said, adding that the country could try again some day —if there is the necessary political maturity and leadership.

But that does not appear near at this moment.

As soon as the results were known, Boric said he would take up again his proposals on pension reform and laws to redistribute wealth, which have been stalled in Congress. On Monday, his administration was already talking about the need to arrive at broad accords, which will be difficult in a divided legislature.

The president spoke Monday about the need to take up issues related to safety and visited one of the capital’s poorest neighborhoods to speak with residents.

Chileans, however, aren’t interested in more words. They want results.

“I don’t know what’s going on, there’s no action, no greater punishments, we see guys in jail and then the next day they’re out again,” said Johanna Anríquez, a 38-year-old public servant who voted with Boric against the new constitution, but remains critical of his administration.

Boric’s administration this year steered an additional $1.5 billion to security and plans to raise the budget another 5.7% in 2024. But it hasn’t been able to reach agreements with opposition lawmakers on security-related reforms.

He has also taken executive action to send more police to poor neighborhoods, but Chileans continue to feel less safe. Crime rates have risen dramatically, even though they remain well below other Latin American countries.

Sociologist and psychologist Kathya Araujo, who wrote various books about the 2019 popular demonstrations in Chile, says it’s uncertain that Chileans will be able to stage protests similar to those, at least in the short term.

“They thought they had to change, that they were going to change society, that (writing a new constitution) was the place for the revolution,” she said. And because of that, after losing they began to break apart.

Many woke up Monday thinking the social struggle of the past several years had amounted to nothing.

“We’re the same, there’s nothing more to do,” Santiago resident Gustavo Fernández said Monday. “With everything that was done … for nothing.”

____

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america