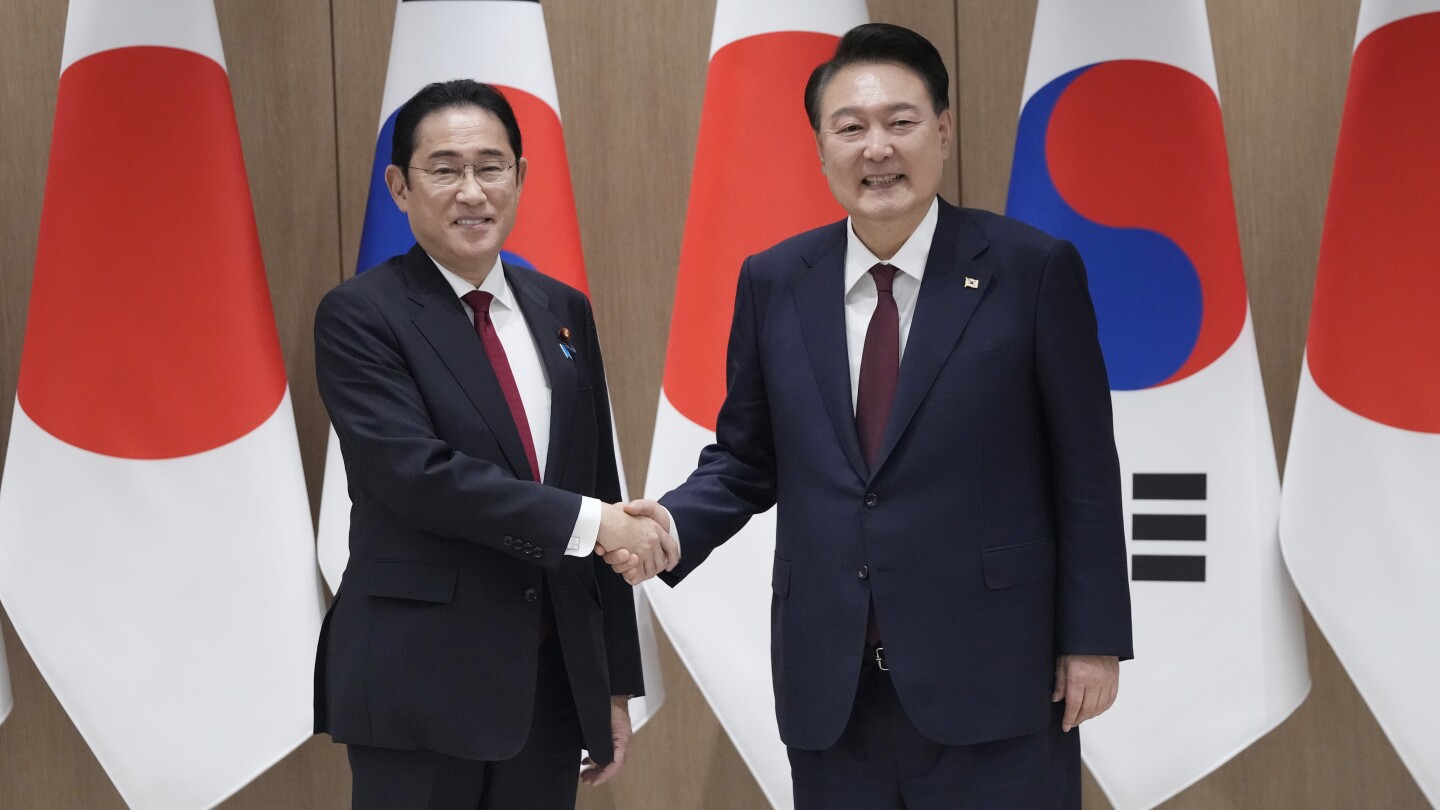

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — Less than a month before leaving office, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is visiting South Korea on Friday to boost warming ties between the traditional Asian rivals, as challenges lie ahead for their cooperation after his departure.

Kishida’s two-day trip was arranged after he “actively” expressed hope for a meeting with conservative South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol to end his term on a high note in bilateral relations, according to Yoon’s office. It said Yoon and Kishida will look back on their achievements in bilateral ties and discuss further cooperation during a meeting Friday, the 12th between the two leaders.

This shows what legacy Kishida wants to leave after three years in office, experts say. He is credited with boosting Japan’s security and diplomatic partnerships with the U.S., South Korea and others but suffered low popularity at home due to his governing party’s political scandals.

“Prime Minister Kishida has put his personal political capital on the line to improve relations with South Korea. With President Yoon, Kishida upgraded bilateral diplomatic and security cooperation and elevated trilateralism with the United States” at a summit at Camp David in the United States last year, said Leif-Eric Easley, professor of international studies at Ewha Womans University in Seoul.

“This farewell summit in Seoul is meant to solidify that legacy,” he said.

Japan and South Korea are both key U.S. allies in Asia, together hosting about 80,000 American troops. Their cooperation is crucial for U.S. efforts to buttress its regional alliances in response to increasing Chinese influence and North Korea’s growing nuclear threat. But ties between Japan and South Korea have suffered periodic setbacks because of grievances stemming from Japan’s 1910-45 colonial occupation of the Korean Peninsula.

Bilateral ties began thawing significantly after Yoon took a contentious step in March 2023 to resolve long-running compensation issues for Koreans who were forced to work for Japanese companies during the colonial period. Kishida later expressed sympathy for the suffering of Korean forced laborers, though he avoided a new, direct apology for the colonization.

The two countries have since revived high-level talks and withdrawn economic retaliatory measures they had imposed on each other during wrangling over the forced laborers. But Yoon’s creation of a South Korean corporate fund to compensate victims of forced labor without Japanese contributions triggered a domestic backlash as his liberal rivals accused him of being submissive to Tokyo.

“If President Yoon is truly the president of the Republic of Korea, he must not let the visit become an occasion to advertise Kishida’s achievements,” said Han Min-soo, a spokesperson for the main liberal opposition Democratic Party. “Our people will no longer tolerate the Yoon Suk Yeol government undermining national interest with a subservient diplomacy toward Japan.”

Yoon has argued that it’s time to move beyond historical disputes and seek better ties with Japan because of shared challenges including the intensifying strategic rivalry between the U.S. and China, North Korea’s advancing nuclear arsenal and supply chain vulnerabilities. Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi said Tuesday that Kishida’s trip will be an important occasion for the two leaders to discuss further bilateral cooperation in an increasingly difficult strategic environment.

Choi Eunmi, a Japan expert at the Seoul-based Asan Institute for Policy Studies, said Kishida’s trip suggests he wants to see the momentum for improved ties continue, whoever becomes Japan’s next prime minister.

No big announcement is expected after Friday’s Yoon-Kishida meeting. The focus of South Korean media attention has been whether Kishida would issue any comments that could help Yoon deal with domestic criticism of his Japan policy.

“If Kishida offers a reconciliatory gesture on history issues during his visit, he could garner goodwill that would be an asset to Japan’s next leader and also help Yoon address domestic critics of his cooperative approach toward Tokyo,” Easley, the professor, said.

Last month, Kishida announced he won’t seek another term, clearing the way for his governing Liberal Democratic Party to choose a new standard bearer in its leadership election on Sept. 27. The winner of that election will replace Kishida as both party chief and prime minister.

Among the leading candidates is former Environment Minister Shinjiro Koizumi, who has frequently visited Tokyo’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine, which honors the country’s about 2.5 million war dead, including convicted war criminals. Japan’s neighbors view the shrine as a symbol of the country’s past militarism.

“If Shinjiro Koizumi wins the race, he will likely maintain (Kishida’s) strategic external policies including toward South Korea. But whether he would continue to go to Yasukuni Shrine will be a key issue,” Choi said. “Can South Korea accept a new Japanese prime minister visiting Yasukuni Shrine? I doubt it.”

Kishida has refrained from visiting and praying at the shrine while prime minister, and instead sent ritual offerings.

Another contender is former Defense Minister Shigeru Ishiba, whose strong comments on Japanese military ambitions could complicate ties with South Korea, Choi said.

In the longer term, South Korea-Japan relations could experience bigger changes if liberals in South Korea win back the country’s presidency after Yoon ends his single five-year term in 2027.