An advanced geothermal project has begun pumping carbon-free electricity onto the Nevada grid to power Google data centers there, Google announced Tuesday.

Getting electrons onto the grid for the first time is a milestone many new energy companies never reach, said Tim Latimer, CEO and co-founder of Google’s geothermal partner in the project, Houston-based Fervo Energy.

“I think it will be big and it will continue to vault geothermal into a lot more prominence than it has been,” Latimer said in an interview.

The International Energy Agency has long projected geothermal could be a serious solution to climate change. It said in a 2011 roadmap document that geothermal could reach some 3.5% of global electricity generation annually by 2050, avoiding almost 800 megatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions per year.

But that potential has been mostly unrealized up until now. Today’s announcement could mark a turning point.

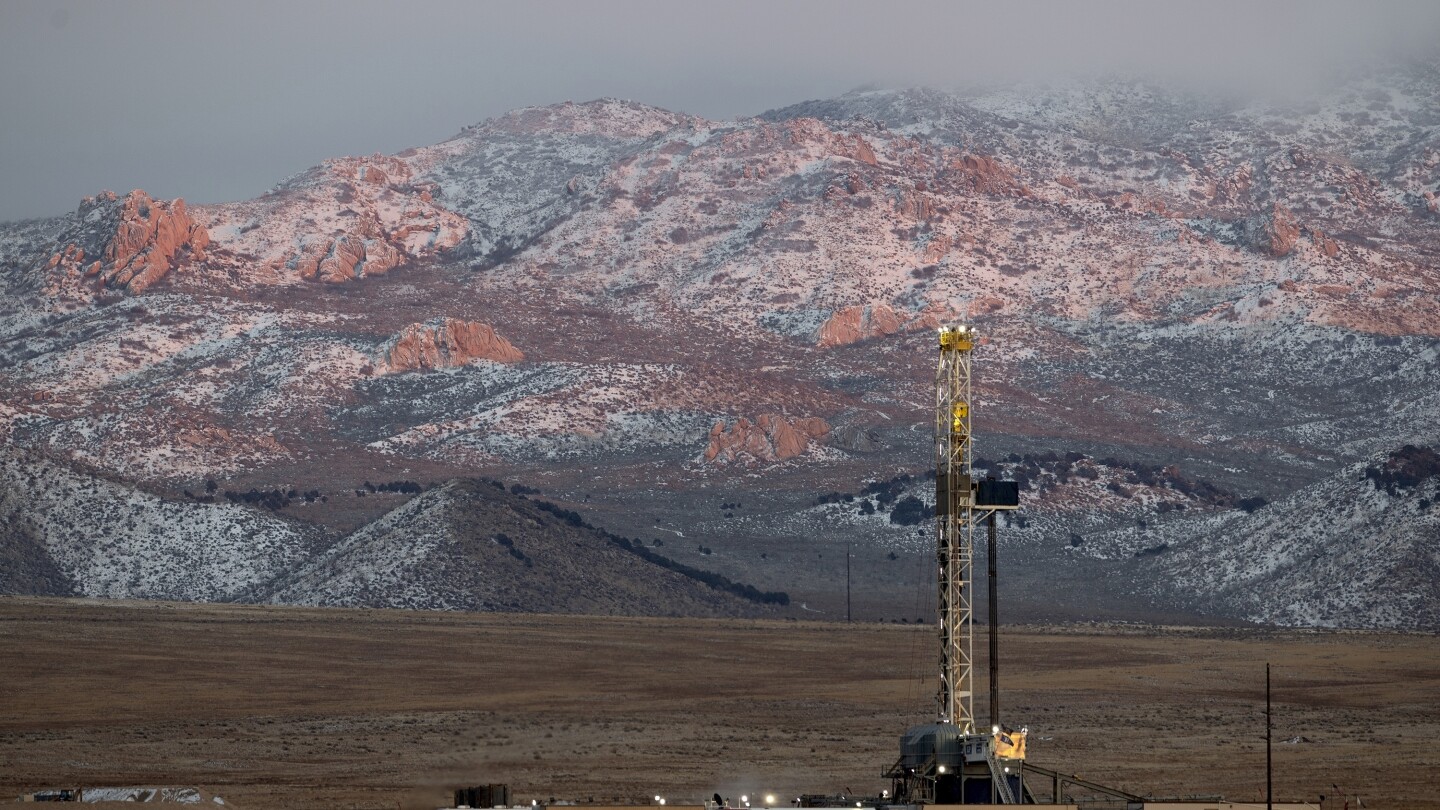

Fervo is using this first pilot to launch other projects that will deliver far more carbon-free electricity to the grid. It’s currently completing initial drilling in southwest Utah for a 400-megawatt project.

Google and Fervo Energy started working together in 2021 to develop next-generation geothermal power. Now that the site near Winnemucca, Nevada is operating commercially, its three wells are sending about 3.5 megawatts to the grid.

The data centers require more electricity than that, so Google signed other agreements for solar and storage too. It has two sites in Nevada, one near Las Vegas and the other near Reno. Michael Terrell, who leads decarbonization efforts globally at Google, said the company is looking at using geothermal energy for other data centers worldwide as a portfolio of carbon-free technologies.

“We’re really hoping that this could be a springboard to much, much more advanced geothermal power available to us and others around the world,” he said.

Google announced back in 2020 that it would use carbon-free energy every hour of every day, wherever it operates, by 2030.

Many energy experts believe huge companies like Google can play a catalytic role in accelerating clean energy.

Terrell noted the company was also an early supporter of wind and solar projects, helping those markets take off.

“It’s a very similar situation. Now that we’ve set a goal to be 24/7 carbon-free energy, we have found it will take more than just wind, solar and storage to achieve that goal,” Terrell said in an interview. “And frankly to get power grids to 24/7 carbon-free energy as well, we’re going to need this new set of advanced technologies in energy. Looking at this deal with Fervo, we saw an opportunity to play a role in helping to take these technologies to scale.”

The United States leads the world in using the Earth’s heat energy for electricity generation, but geothermal still accounts for less than half a percent of the nation’s total utility-scale electricity generation, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. In 2022, that geothermal power came from California, Nevada, Utah, Hawaii, Oregon, Idaho and New Mexico.

Those are states traditionally thought of as having geothermal potential because there are reservoirs of steam or very hot water close to the surface in the West.

But Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said earlier this year that advances in enhanced geothermal systems will help introduce this form of energy in regions where it’s been thought to be impossible. Granholm was announcing funding for the industry.

Last year, the Energy Department launched an effort to achieve “aggressive cost reductions” in enhanced geothermal systems. This month, in announcing $44 million to advance geothermal deployment nationwide, DOE said the United States has potential for 90 gigawatts of geothermal electricity — the equivalent of powering more than 65 million American homes — by 2050.

Enhanced geothermal companies, including Fervo, are now going after heat deeper below ground, unlocking potential in many more places. Latimer is a former drilling engineer in the oil and gas industry.

Drilling technology and practices drastically improved during the shale boom that transformed the United States into a top oil and gas producer and exporter. But there has been very little tech transfer from the oil and gas industry to geothermal, said Sarah Jewett, vice president of strategy at Fervo.

“They were using all of the old, for lack of a better word, janky stuff from old-school oil and gas development,” she said. “We basically just went to the oil field service companies and said, ‘Give us all your best stuff.’ And we have been using all of the modern drilling technology to do our development.” That has led to far greater efficiency and lower cost, she said.

In a presentation at ClimateTech 2023 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Latimer talked about how Fervo is pioneering horizontal drilling in geothermal reservoirs. In Nevada, Fervo drilled some 8,000 feet down, turned sideways and drilled about 3,250 feet horizontally.

By drilling horizontally, Fervo can reach much more of the hot reservoir, instead of having to have to drill many vertical wells.

Fervo pumps cold water down an injection well, then over hot rock underground to another well, the production well. The path between is created by fracking, or fracturing the rock. The water heats up to nearly 400 degrees Fahrenheit (200 degrees Celsius) before returning to the surface. Once there, it transfers its heat to another liquid with a low boiling point, creating steam. The pressure of steam expanding spins a turbine to produce electricity like in a coal or natural gas-fired plant. The geothermal water, now cooled, is put back down the injection well to start the cycle again, in a closed-loop system.

Well tests this summer were very favorable, according to Fervo. Latimer wants to replicate them now in as many places as possible, as quickly as possible, to help transition away from coal, oil and natural gas to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The venture capital firm DCVC invested $31 million in Fervo last year, said Rachel Slaybaugh, a partner there. They did it, she said, because Fervo was ready to add power to the grid while competitors weren’t there yet. Slaybaugh said it’s a plus that Latimer used to run a drill rig— it was the right team, who knew what kind of company they were building.

Both Fervo and Google said geothermal is valuable as an “always-on” clean technology that can be scaled up before 2030 as the world tries to cut its greenhouse gas emissions. Fervo’s next project, in Beaver County, Utah is slated to begin delivering clean power to the grid in 2026 and reach full production in 2028.

“This is unlocking something deeply sought after in the market today as we transition away from fossil fuels, and that is, round-the-clock renewable energy,” Jewett said.

___

Associated Press climate and environmental coverage receives support from several private foundations. See more about AP’s climate initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.