KABUL, Afghanistan (AP) — Yunis Safi, a businessman in Kabul, knows very well the importance of showing off your phone if you want something done.

“In Afghanistan, your phone is your personality,” he said, smiling, a jewel-encrusted ring on each hand. One boasts an emerald, the other a fat Russian diamond. “When you go to a meeting with the government, the better your phone, the more they respect you.”

Safi runs a phone shop in the posh Shar-e-Naw neighborhood. An armed guard stands outside. The iPhone 15 Pro Max adorns the shop shelves, retailing for $1,400. He has customers ready to part with this sum of money, which may come as a surprise to some given the country’s economic woes and more than half the population relying on humanitarian aid to survive.

Afghanistan’s finances were on shaky ground even before the Taliban seized power in 2021. The budget relied heavily on foreign aid and corruption was rife. The takeover sent Afghanistan’s economy into a tailspin, billions in international funds were frozen, and tens of thousands of highly skilled Afghans fled the country and took their money with them.

But, even amid difficult conditions, some businesses are making money out of Taliban rule.

Safi has tapped into a diverse consumer base — the ones hungry for the latest iPhone release and those happier with simple handsets, which make up the bulk of his sales and sell for between $20 and $200.

The Taliban used to attack phone towers and threaten telecom companies, accusing them of colluding with United States and other international forces in helping track insurgents’ movements through mobile phone signals. Now, they’re investing in the 4G mobile networks.

The Communications Ministry says 2 million new SIM cards have been issued in the past two years and that subscriber numbers are increasing. Ministry spokesperson Enayatullah Alokozai said the government was plowing $100 million into the telecom sector and had fully restored hundreds of towers.

There are 22.7 million active SIM cards in a country of 41 million people. Of these, 10 million are for voice calls and the rest are for mobile internet.

According to Trade Ministry figures, phone imports have risen. More than 1,584 tons of phones came into Afghanistan in 2022. Last year, it was 1,895 tons.

Safi said he has many Taliban customers and it’s the younger ones who prefer iPhones. “Of course they need smartphones. They use social media, they like making videos. The iPhone has better security than Samsung. The camera resolution, processor, memory are all better. Afghans use their smartphones like anyone else.”

Safi has the iPhone 15 Pro Max, wears an Apple Watch Ultra and owns three cars.

Business was bad immediately after the Taliban takeover but it’s improving, Safi said. “The people buying the new release iPhones are the ones with relatives abroad sending money to Afghanistan.”

Remittances are a lifeline, although they’re less than half of what they were before the Taliban took power and the banking sector collapsed.

At the raucous Shahzada Market in Kabul, hundreds of money exchangers clutch stacks of the local currency, the afghani, and noisily hawk their wares. They occupy every floor, stairwell, nook and cranny.

Abdul Rahman Zirak, a senior official at the money exchange market, estimates that $10 million changes hands daily. The diaspora sends mostly U.S. dollars to families, who exchange it for the afghani.

There used to be more ways to send money to Afghanistan before the Taliban seized control. But there are no more links to SWIFT or international banking and that’s a major reason why business is brisk at the market, he said.

“The work of money exchangers has increased and strengthened,” Zirak said. “Money transfers come from Canada, the U.S., Europe, Australia, Arab nations and other neighboring countries.”

Trade becomes hectic during the holidays. During the holy month of Ramadan, 20,000 people visited the market daily and it took more than 90 minutes to enter, he said.

“If the sanctions are removed and the assets are unfrozen, then maybe our business will decrease. But I don’t see that happening. Many don’t have bank accounts. Unemployment is high, so people send money to Afghanistan. Our business will be needed for years to come.”

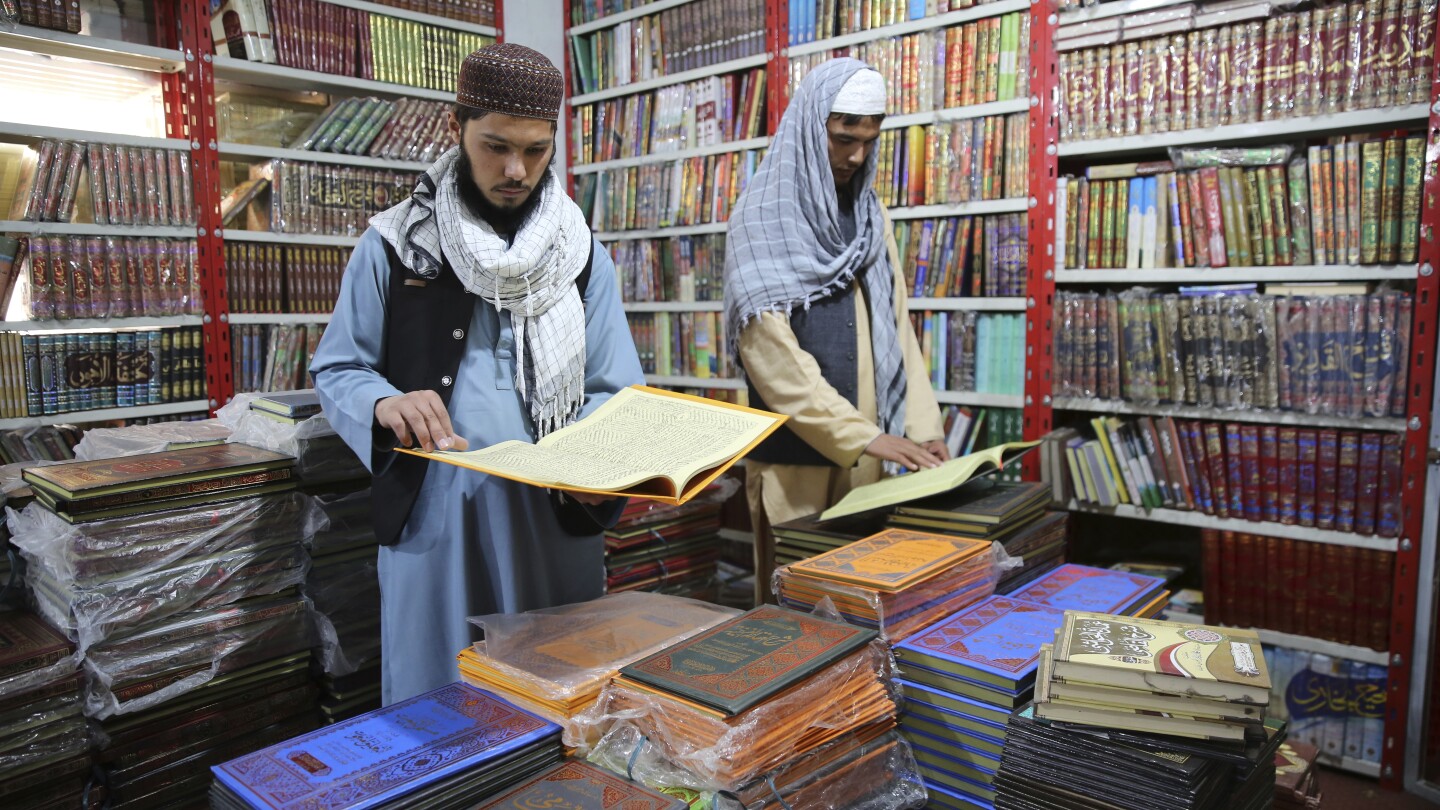

Irfanullah Arif, who runs Haqqani Books, a specialist retailer of Islamic texts, is also upbeat about his fortunes. The majority of his customers are teachers and students at religious schools, or madrassas.

There are at least 20,000 madrassas in Afghanistan. The Taliban want to build more. Last year, the supreme leader reportedly ordered the recruitment of 100,000 madrassa teachers.

While Arif’s business suffered like everyone else’s in the chaotic aftermath of the takeover, there was another reason. “All the students left the madrassas and went to work for the (Taliban) government,” said Arif.

The Taliban’s push for religious education has given him some relief. Last year, he sold 25,000 textbooks.

But there’s a price to pay for success. Arif imports everything and the Taliban are laser-focused on collecting revenue, even on Islamic literature.

Arif pays a tax of 170 afghanis ($2.36) on a carton of 100 books, the shipping cost for which is 500 afghanis ($6.95). Taxes on his bookstore have tripled under Taliban rule.

“That’s why books are expensive in Afghanistan,” he sighed. “With the increase of madrassas, our trade has gone up, but so have the taxes.”